9: Scheduling

Scheduling Concept

Why we need scheduling? For multitasks and concurrency. Scheduling is only useful when there is not enough resources.

- preemption is the basic assumption for fine-grained scheduling (time interrupts)

- who schedules processes/threads?

- mostly by OS

- user-level thread libraries schedule the threads by themselves

Scheduling Policy Goals

- minimize response time

- maximize throughput

- maximize operations (or jobs) per second

- throughput related to response time, but not identical

- minimizing response time will lead to more context switching than if you only maximized throughput

- Two parts to maximize throughput

- minimize overhead (for example, context-switching)

- efficient use of resources (CPU, disk, memory, etc)

FCFS

First-Come, First-Served (FCFS).

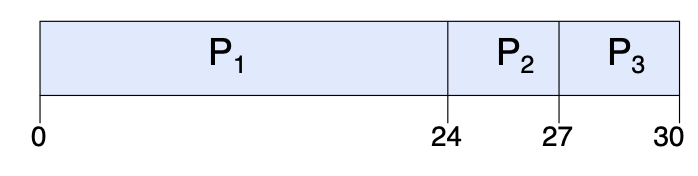

For example, suppose processes arrive in the order: \(P_1\), \(P_2\), \(P_3\).

| Process | Burst Time |

|---|---|

| \(P_1\) | \(24\) |

| \(P_2\) | \(3\) |

| \(P_3\) | \(3\) |

The Gantt chart for the schedule is:

- waiting time for \(P_1 = 0\), \(P_2 = 24\), \(P_3 = 27\)

- average waiting time: \((0 + 24 + 27) / 3 = 17\)

- average completion time: \((24 + 27 + 30) / 3 = 27\)

Def. Convoy effect: short process behind long process

SJF

Def. Shortest Job First (SJF): always schedule the job with the shortest remaining time (so sometimes it’s also called shortest-remaining-time-first, SRTF).

It theoretically minimizes the average response time, why?

Cons:

- starvation. If small jobs keep coming, the long jobs will not be served. Fairness issue

- implementation. It’s hard to know the task remaining time

RR

Def. Round Robin (RR): each process gets a small unit of CPU time (time quantum), usually 10-100 milliseconds. After quantum expires, the process is preempted and added to the end of the ready queue.

\(n\) processes in ready queue and time quantum is \(q\) \(\Rightarrow\)

- each process gets \(1 / n\) of the CPU time

- in chunks of at most \(q\) time units

- no process waits more than \((n - 1)q\) time units

For example

| Process | Burst Time |

|---|---|

| \(P_1\) | \(53\) |

| \(P_2\) | \(8\) |

| \(P_3\) | \(68\) |

| \(P_4\) | \(24\) |

- quantum is \(20\)

the Gantt chart is

| \(P_1\) | \(P_2\) | \(P_3\) | \(P_4\) | \(P_1\) | \(P_3\) | \(P_4\) | \(P_1\) | \(P_3\) | \(P_3\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(\text{0-20}\) | \(\text{20-28}\) | \(\text{28-48}\) | \(\text{48-68}\) | \(\text{68-88}\) | \(\text{88-108}\) | \(\text{108-112}\) | \(\text{112-125}\) | \(\text{125-145}\) | \(\text{145-153}\) |

- the average waiting time is \(((0 + 68 - 20 + 112 - 88) + (20 - 0) + (28 - 0 + 88 - 48 + 125 - 108) + (48 - 0 + 108 - 68 )) / 4 = 66.26\)

- the average completion time is \((28 + 112 + 125 + 153) / 4 = 104.5\)

Thus, RR pros and cons:

- better for short jobs

- context switch time adds up for long jobs

How do we choose time slice?

- too large: response time suffers (infinite, falls back to FCFS)

- too small: throughput suffers

CPU 越强,时间片切片可以设置越小

Comparing FCFS and RR

Assuming zero cost context switching time, is RR always better than FCFS? We consider that existing 10 jobs, each take 100s of CPU time, RR scheduler quantum of 1s, all jobs start at the same time, and all jobs have same length.

Obviously, RR is bad (compute completion time). Also, cache state must be shared between all jobs with RR but can be devoted to each job with FCFS.

Strict Priority Scheduling

Def. Strict Priority Scheduling: always executes highest priority runnable jobs to completion. Each queue can be processed in RR with some time quantum.

Problems:

- starvation: lower priority jobs don’t get to run because higher priority jobs

- deadlock: priority inversion

- not strictly a problem with priority scheduling, but happens when low priority task lock needed by high priority task

Def. Dynamic Priority: adjust base level priority up or down based on heuristics about interactivity, locking, burst behavior, etc…

Earliest Deadline First (EDF)

- tasks periodic with period \(P\) and computation \(C\) in each period: \((P, C)\)

- preemptive priority based dynamic scheduling

- each task is assigned a (current) priority based on how close the absolute deadline is

- the scheduler always schedules the active task with the closest absolute deadline

Scheduling Fairness

fairness gained by hurting avg response time

How to implement fairness?

- could give each queue some fraction of the CPU

- what if one lone running job and 100 short running ones?

- like express lanes in a supermarket, sometimes express lanes get so long, get better service by going into one of the other lines

- could increase priority of jobs that don’t get service

- what is done in some variants of UNIX

- as system gets overloaded, no job gets CPU time, so everyone increases in priority \(\Rightarrow\) interactive jobs suffer

If every tasks need the same resource, fairness is easy: RR.

Def. Max-Min Fairness: iteratively maximize the minimum allocation given to a particular process (or threads/users/applications) until all resources are assigned. (mostly used in network)

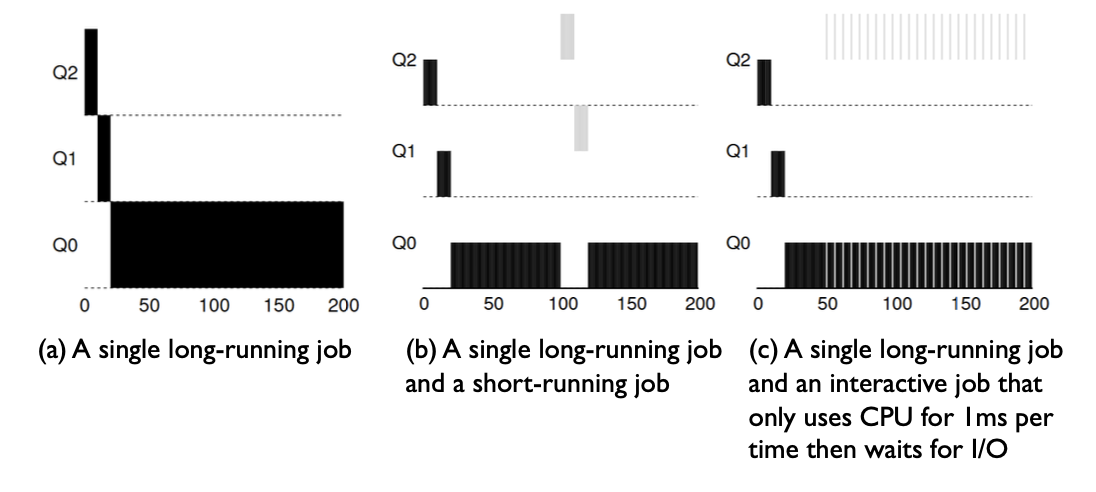

Multi-Level Feedback Queue (MFQ) Scheduling

Def. Multi-Level Feedback Queue (MFQ) Scheduling: achieves responsiveness (short jobs quickly as SJF), low overhead (minimizing the preemptions and scheduling decision time), and starvation free (as RR), and fairness (approximately max-min fair share).

Assuming a mix of two kinds of workloads

- interactive tasks (e.g.waiting for user keyboard input): using CPU for a short time, then yield for I/O waiting. Low latency is critical.

- CPU intensive tasks (e.g. compressing files): using CPU for a long period of time. The response time often does not matter much.

A naive version of MFQ: maintaining many tasks queues with different priorities, and use following schedule rules

- rule 1: if \(\text{priority A} > \text{priority B}\), \(A\) runs

- rule 2: if \(\text{priority A} = \text{priority B}\), \(A\) and \(B\) run in RR

The key here is how to set the priority.

- intuitively, if a job repeatedly relinquishes the CPU while waiting for input from the keyboard, it shall be kept in high priority

- otherwise, if a job uses CPU intensively for long periods of time, its priority shall be reduced

Our solution: assign a quota for each job at a given priority level, and reduces its priority once the quota is used up.

- rule 3: when a job enters the system, it is placed at the highest priority (the topmost queue)

- rule 4a: if a job uses up its allotment while running, its priority is reduced (i.e., it moves down one queue)

- rule 4b: if a job gives up the CPU (for example, by performing an I/O operation) before the allotment is up, it stays at the same priority level (i.e., its allotment is reset)

There are many issues with this naive version of MFQ

- starvation: if there are too many interactive jobs in the system, they will consume all CPU time, and thus long-running jobs will starve

- solution 1, rule 5: after some time period \(S\), move all the jobs in the system to topmost queue

- \(S\) shall be neither too large or too small

- solution 2: time slice across queues

- each queue gets a certain amount of CPU time

- countermeasure: user action that can foil intent of OS designers, e.g., put in a bunch of meaningless I/O to keep job’s priority high

- how to parameterize the scheduler: how many queues should there be? how big should the time slice be per queue?

To further extend the MFQ design: each queue has its own scheduling parameters or even different algorithms

- e.g. foreground - RR, background - FCFS

- sometimes multiple RR priorities with quantum increasing exponentially (highest: 1ms, next: 2ms, next: 4ms, etc..)

Adjust each job’s priority as follows (details vary)

- job starts in highest priority queue

- if timeout expires, drop one level

- if timeout doesn’t expire, push up one level (or stay at the same one)

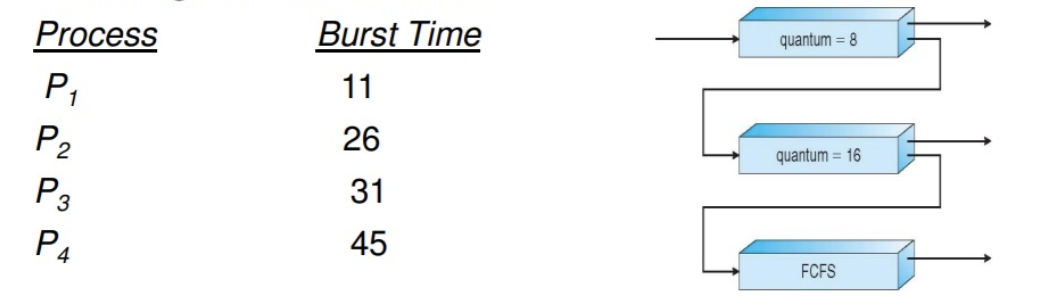

A test, assume we have \(4\) processes in a system with multilevel feedback queue scheduling policy. All the process arrived at time \(0\) and located in the highest level queue in the order of their IDs (\(1\) to \(4\)).

(1). Calculate the average waiting time and average turnaround time.

| \(P_1\) | \(P_2\) | \(P_3\) | \(P_4\) | \(P_1\) | \(P_2\) | \(P_3\) | \(P_4\) | \(P_2\) | \(P_3\) | \(P_4\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(\text{0-8}\) | \(\text{8-16}\) | \(\text{16-24}\) | \(\text{24-32}\) | \(\text{32-35}\) | \(\text{35-51}\) | \(\text{51-67}\) | \(\text{67-83}\) | \(\text{83-85}\) | \(\text{85-92}\) | \(\text{92-113}\) |

The average waiting time is:

- \(P_1 = 0 + 32 - 8 = 24\)

- \(P_2 = 8 + 35 - 16 + 83 - 51 = 59\)

- \(P_3 = 16 + 51 - 24 + 86 - 67 = 62\)

- \(P_4 = 24 + 67 - 32 + 93 - 83 = 69\)

The average completion time is:

- \(P_1 = 35\)

- \(P_2 = 85\)

- \(P_3 = 92\)

- \(P_4 = 113\)

(2). If a new process \(P_5\) enters the system at time \(35\) how the Gantt chart is going to change?

需要注意的是,\(P_5\) 并不会打断此时的 \(P_4\),也就是放后面,因为二者处于同一优先级

Fair-Share Scheduler

This type of scheduler aims to guarantee that each job obtain a certain percentage of CPU time.

Lottery Scheduling

- give each job some number of lottery tickets

- on each time slice, randomly pick a winning ticket

- on average, CPU time is proportional to number of tickets given to each job (but not deterministically)

How to assign tickets?

- to approximate SRTF, short running jobs get more, long running jobs get fewer

- to avoid starvation, every job gets at least one ticket (everyone makes progress)

Advantage over strict priority scheduling: behaves gracefully as load changes

- adding or deleting a job affects all jobs proportionally, independent of how many tickets each job possesses

Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS)

The default Linux scheduler sin v2.6.23. The goal of CFS: to fairly divided a CPU evenly among all competing processes.

CFS uses a counting-based technique known as virtual runtime

- as each process runs, it accumulates virtual runtime, e.g., in proportion with the physical (real) time

- when a scheduling decision occurs, CFS will pick the process with the lowest virtual time to run next

How does CFS know when to stop the running process? The scheduling time slice.

Real-Time Scheduling

Scheduling on Multiprocessor

What’s wrong with a centralized MFQ?

- contention for the MFQ lock

- teh lock could become a bottleneck especially with large number of processors

- cache coherence overhead

- the MFQ data structure will be modified often and cause miss when a processor gets its lock to use MFQ

- limit cache reuse

- a thread is likely to be scheduled on different processors, so the L1 cache needs to be fetched from the memory again

Modern OSes use per-processor MFQ

Def. Affinity Scheduling: a thread is always scheduled to the same processor. Rebalancing across processors only happens when necessary.