Chapter 17: Transactions

Transaction Management

A single user’s access to the database (DB) is represented as one or more transactions executed by the Database System (DBS), including operations such as select, insert, delete, and update.

- Transactions are the fundamental logical units of the Database Application System (DBAS) and the basic units managed by the Database Management System (DBMS).

Multi-user concurrent access to the database is represented as one or more transactions executed concurrently by the DBS.

If more than two transactions access to shared data \(Q\), who ensures data integrities (ACID)?

- Recovery-management in DBMS is responsible for atomicity and durability.

- Concurrency-control in DBMS is responsible for isolation and consistency.

Transaction Concept

- Def. The transaction is a unit of DBAS, executing accesses and updates various data items in DB.

- Def. A transaction consists of operations delimited by statements

- begin transaction and end transaction.

- operations: read or write on DB.

A transaction is initialized by an application program written in

- DML, such as SQL.

- programming languages, such as C++ embedded accesses.

Transaction Model

Each data access, such as select, update in SQL is translated/decomposed into read and write operations. This means DBMS executes read and write operations to fulfill data access in transactions.

DBMS allocates local buffer in main memory as working area. THe DB permanently resides on disk, but some portion is temporarily residing in buffer in main memory.

- Def.

read(X)- transfers data item

Xfrom DB files on disk buffer or disk to a variable, also calledX, in the local buffer, belonging to a transaction that executes the read operation.

- transfers data item

- Def.

write(X)- transfers the value in variable

Xin local buffer back to data itemXin DB files on disk, belonging to a transaction that executes the write operation.

- transfers the value in variable

Note: the write operation does not result in the immediate update of data on disk. It may be temporarily stored in disk buffer.

Consistency

Execution of transactions in isolation preserves consistency of DB. DB is in a correct DB state, before and after the transaction execution.

- Def. DB state: contents of tables in DB or DB instance

- Def. Consistency/correctness: integrity constraints are not violated.

Consistency requirements include

- Explicit integrity constraints such as primary key and foreign key

- Implicit integrity constraints, for example, sum of balances of all accounts minus sum of loan amounts must equal value of cash-in-hand

The DB may be temporarily inconsistent during transaction execution, but the DB must be consistent when transaction completes successfully.

Atomicity

Either all operations of transaction are reflected/persisted or none. Ensure that updates of a partially executed transaction are not reflected.

Isolation

Def. Even though multiple transactions execute concurrently, all transactions seem to execute serially, so the consistency is preserved.

Each transaction is unaware of other transactions executing concurrently

Isolation guarantees

- correctness of concurrent execution of multiple transactions

- concurrency control ensures the isolation

Isolation can be ensured by running transactions serially, one after the other.

Durability

Def. Once the transaction has completed, the updates to the database by the transaction must persist even if there are software or hardware failures.

The modified values of data items in buffer should be reflected (write to DB on disk).

ACID Guaranteeing

ACID mechanisms in DBS

- Atomicity: transaction management/recovery management component.

- Consistency: integrity constraints; testing mechanism in DBMS.

- Isolation: concurrency control component.

- Durability: recovery management component.

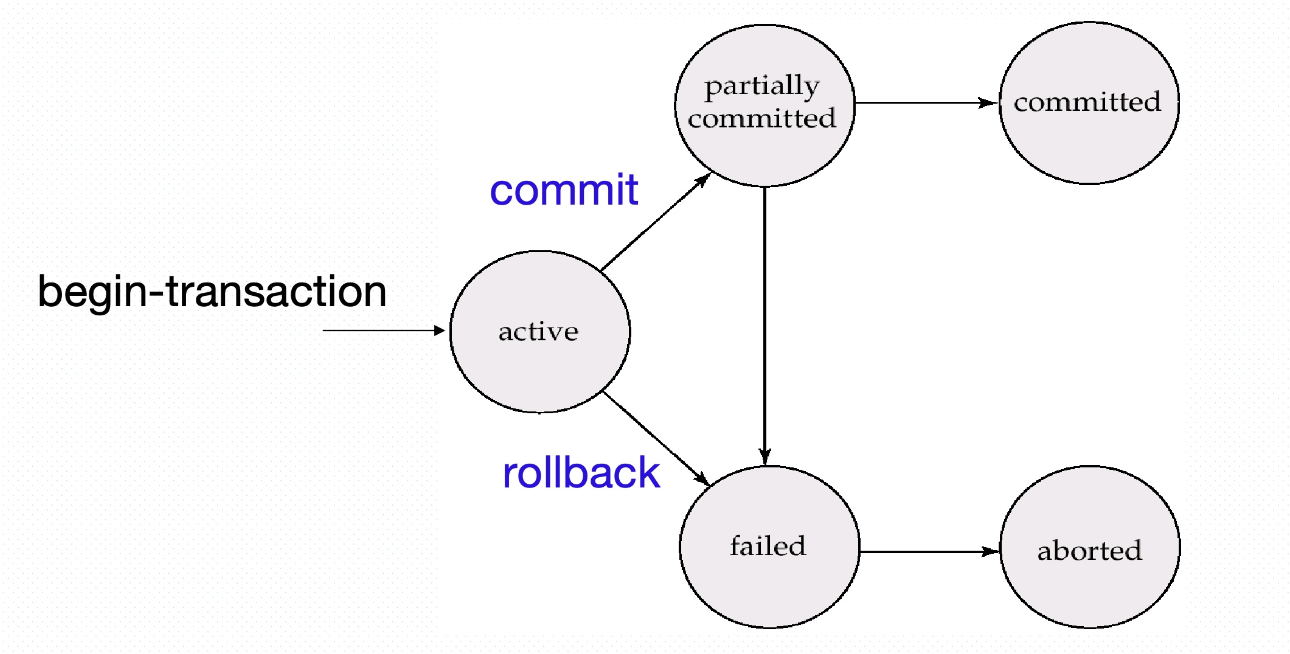

Transaction Atomicity and Durability (State Model)

- Def. A transaction is termed aborted, if it may not complete its execution successfully.

- Def. A transaction is said to be committed, if it completes its execution successfully.

- Def. Once the changes by anaborted transaction has been undone, the transaction is said to be rollback.

- Def. A transaction is said to have terminated, if it has either committed or aborted.

Transaction States

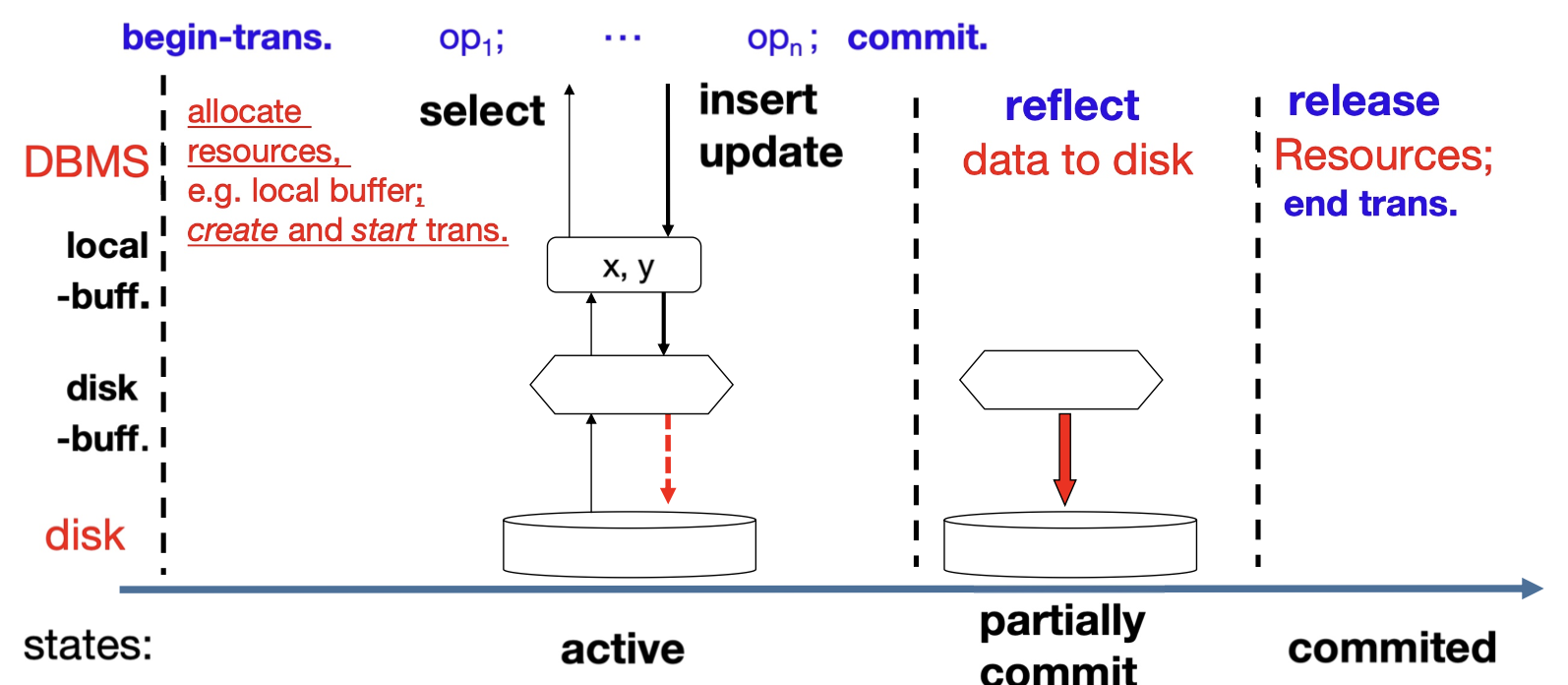

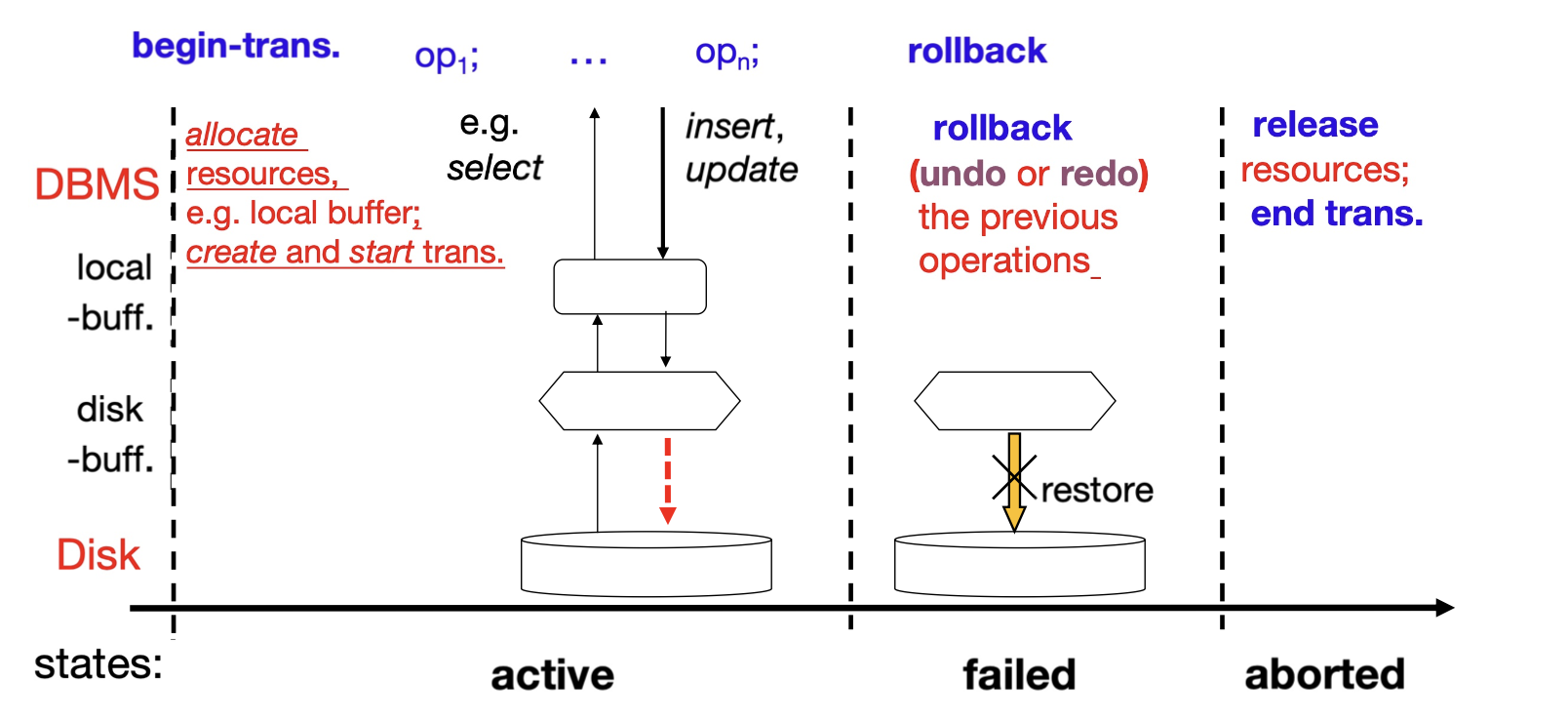

Transaction states during its life cycle

- active: the initial state

- the initial state, the transaction stays while it is executing from

begin-transaction - the transaction is created after

begin-transactionis submitted - Note: transaction operations are executed, but the modifications on DB issued by operations may only stored temporally in the disk buffer. Not reflected to DB file on disks immediately.

- the initial state, the transaction stays while it is executing from

- partially committed: after the final statement commit, executed

- the influences that the transaction operations have made are reflected from the disk buffer to the DB file

- failed: the normal execution can no longer proceed

- the transaction is rolled back to restore DB to the state prior to the start of the transactions

- aborted: after the transaction has been rolled back the DB restored to its state prior to the start of the transaction

- two options after aborted:

- restart the transaction: only if no internal logical error

- kill the transaction

- the transaction

- releases the resources occupied

- reports ot its user that the transaction is aborted

- terminated (quits DBS)

- the cycle life of the transaction is ended

- two options after aborted:

- committed: after successful completion (all results have been reflected to the DB file in the partial committed state). Then the transaction

- releases the resources occupied

- terminated (quits DBS)

- the cycle life of the transaction is ended

Transaction Isolation

Concurrent execution of transactions allows high throughput and resource utilization, reducing waiting time. But transactions may contain operations on shared data, the different schedules may result in different final DB states.

*Concurrent Executions and Scheduling

Def. Schedule on a set of concurrent transactions, specifies the order of the executed operations of concurrency transactions.

- consists of all operations of transactions

- preserves the order of operations in each individual transaction

Note:

- A transaction that succeeds in execution will have a commit instruction as the last statement

- A transaction that fails in execution will have an abort instruction as the last statement

Here is an example illustrating two scheduling: serial schedule and concurrent schedule. Suppose there are two transactions

- \(T_1\): transfer \(50\) funds from \(A\) to \(B\)

- \(T_2\): transfer \(10\%\) of the balance from \(A\) to \(B\)

- Initializing value of \(A = 1000\), \(B = 2000\)

If we apply serial schedule, obviously, different sequence of \(T_1\), \(T_2\) results in different final values of \(A\) and \(B\). The following illustrate the condition that we execute \(T_1\) first.

| \(t\) | transaction | values |

|---|---|---|

| \(T_1\) | read(\(A\)) \(A := A - 50\) write(\(A\)) read(\(B\)) \(B := B + 50\) write(\(B\)) commit |

\(A = 950\) \(B = 2050\) |

| \(T_2\) | read(\(A\)) \(\text{temp} := A \times 0.1\) \(A := A - \text{temp}\) write(\(A\)) read(\(B\)) \(B := B + \text{temp}\) write(\(B\)) commit |

\(A = 855\) \(B = 2145\) |

If we execute \(T_2\) first, the final value: \(A = 850\), \(B = 2150\).

What about applying concurrent schedule? The core idea is allowing a transaction executes when another transaction is executing. Here is an example on \(T_1\) and \(T_2\). We suppose we execute \(T_1\) first.

| \(t\) | transaction | values |

|---|---|---|

| \(T_1\) | read(\(A\)) \(A := A - 50\) write(\(A\)) |

\(A = 950\) |

| \(T_2\) | read(\(A\)) \(\text{temp} := A \times 0.1\) \(A := A - \text{temp}\) write(\(A\)) |

\(A = 855\) |

| \(T_1\) | read(\(B\)) \(B := B + 50\) write(\(B\)) commit |

\(B = 2050\) |

| \(T_2\) | read(\(B\)) \(B := B + \text{temp}\) write(\(B\)) commit |

\(B = 2145\) |

Note, assuming, read fetches data directly from DB file on disk.

Serializable

To identify whether a concurrent schedule on transactions is right (this schedule is equivalent to a serial schedule).

Basic assumption:

- each transaction preserves DB consistency

- serial execution of transactions preserves DB consistency

Def. A schedule is serializable if it is equivalent to a serial schedule.

Conflict serializable

Two transactions \(T_i = \{l_i\}\), \(T_j = \{l_j\}\), and schedule \(S\) on \(T_i\) and \(T_j\).

- Def. \(l_i\) of transactions \(T_i\) and \(l_j\) of \(T_j\) are conflict, if and only if for some item \(Q\) accessed by both \(l_i(Q)\) and \(l_j(Q)\), at least one of these two instructions is write(\(Q\)).

- Def. \(S\) and \(S'\) are conflict equivalent if the schedule \(S\) can be transformed into \(S'\) by a series of swaps of non-conflicting instructions/operations.

Note:

- Only swapping of two operations/instructions \(l_i\) and \(l_j\) that belong to two different \(T_i\) and \(T_j\) respectively are permitted

- Swapping should not change the orders of instruction in each transaction

- Swapping should not change orders of conflict instruction executing \(S\)

Def. A concurrent schedule \(S\) is conflict serializable if it is conflict equivalent to a serial schedule \(S'\)

*Identification of Conflict Serializable

- Starting from the concurrent \(S\), maintaining executing orders of conflicting, swapping executing orders of non-conflicting operations in \(S\). Observing whether a serial \(S'\) can be obtained.

- Precedence graph

Def. Precedence graph \(G(S)\) for the given transactions \(T_i\), \(T_j\),

- direct graph \(G(V, E)\), where the vertices are transactions

- arc from \(T_i \to T_j\), for which one of three conditions holds

- \(T_i\) executes write(\(Q\)) before \(T_j\) executes read(\(Q\))

- \(T_i\) executes read(\(Q\)) before \(T_j\) executes write(\(Q\))

- \(T_i\) executes write(\(Q\)) before \(T_j\) executes write(\(Q\))

Def. A schedule is conflict serializable if and only if its precedence graph is acyclic.

For example,

| \(t\) | \(T_1\) | \(T_2\) | \(T_3\) | \(T_4\) | \(T_5\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(1\) | read(\(X\)) | ||||

| \(2\) | read(\(Y\)) | ||||

| \(3\) | read(\(Z\)) | ||||

| \(4\) | read(\(V\)) | ||||

| \(5\) | read(\(W\)) | ||||

| \(6\) | read(\(W\)) | ||||

| \(7\) | read(\(Y\)) | ||||

| \(8\) | write(\(Y\)) | ||||

| \(9\) | write(\(Z\)) | ||||

| \(10\) | read(\(U\)) | ||||

| \(11\) | read(\(Y\)) | ||||

| \(12\) | write(\(Y\)) | ||||

| \(13\) | read(\(Z\)) | ||||

| \(14\) | write(\(Z\)) | ||||

| \(15\) | read(\(U\)) | ||||

| \(16\) | write(\(U\)) |

graph TD

A[T1] --> B[T2]

B --> C[T4]

A --> D[T3]

D --> C

A --> C

E[T5]

Construction of Conflict Serializable Schedule

Construct a serializable \(S'\), conflict equivalent to s serializable schedule \(S\).

- starting from a given schedule \(S\)

- maintaining executing orders of conflicting operations in \(S\)

- swapping executing orders of non-conflicting operations in \(S\)

- resulting in a conflict serializable \(S'\)

Transaction Isolation and Atomicity

When transaction \(T_i\) fails, operations \(T_j\) that depends on \(T_i\) already executed should be rollback/undone/aborted/canceled (ensures atomicity).

*Recoverability

Def. Recoverable schedule is a schedule for each pair of \(T_i\) and \(T_j\). If \(T_j\) reads data item \(Q\) previously written by \(T_i\), commit operations of \(T_i\) appears before commit operation of \(T_j\).

Consider relation schemas: SC(S#, C#, grade), and MaxGrade(C#, maxG). What’s more, check grade in SC (\(0 \leq\) grade \(\leq 100\)).

The transactions are

| \(T_i\) | \(T_j\) |

|---|---|

| begin transaction insert into SC value (103, 2, 97); |

|

| begin transaction insert into MaxGrade(C#, maxG) select C#, max(grade) from SC group by C#; commit |

|

| update SC set grade = grade + 5; commit |

SQL server can use SET XACT_ABORT {ON | OFF}

- If

ON, entire transaction will terminate and rollback, recoverable schedule - If

OFF, only rollback where fails, and transaction will continue, probably non-recoverable schedule - Default

OFF

Here is an example of absolutely non-recoverable schedule. The transactions are:

| \(T_1\) | \(T_2\) |

|---|---|

| read(\(A\)) | |

| write(\(A\)) | |

| read(\(A\)) | |

| commit | |

| read(\(B\)) | |

| commit |

If \(T_1\) is aborted after \(T_2\) has been committed, the value if the item \(A\) will be rollback to its old value before \(T_1\) executes. But \(T_2\) has read the new value of the data item \(A\) and has been committed.

Cascadeless Schedules

Def. Cascading rollback: a single transaction failure leads to series of transactions rollbacks.

Cascading rollback is undesirable, because undoing of the previous works.

Def. Cascadeless schedules are the schedules that cascading rollback cannot occur. For each pair of \(T_i\) and \(T_j\), where \(T_j\) reads \(Q\) previously written by \(T_i\), the commit operations of \(T_i\) appears before the read operation of \(T_j\).

Cascadeless schedule is also recoverable, but a recoverable may not be a cascadeless schedule.

例题

Consider transaction \(T_1\), \(T_2\), \(T_3\) and \(T_4\) under \(S\). which concurrently access relational tables Student(stuID, stuName, age, height) and Grade(stuID, cosID, grade)

| \(T_1\) | \(T_2\) | \(T_3\) | \(T_4\) |

|---|---|---|---|

| begin transaction | |||

| begin transaction | |||

| update Student set stuName = ‘Li’ where stuID = 10 |

|||

| begin transaction | |||

| update Student set age = age + 1 where stuID = 20 |

|||

| select age from Student where stuID = 50 |

|||

| begin transaction | |||

| update Student set height = height + 5 where stuID = 30 |

|||

| update Grade set grade = grade + 1 where stuID = 40 and cosID = 10 |

|||

| select stuName from Student where stuID = 10 |

|||

| commit | |||

| commit | |||

| select stuID, grade from Grade where stuID = 40 and cosID = 10 |

|||

| commit | |||

| select height from Student where stuID = 30 |

|||

| commit |

problem:

(1). Construct the precedence graph for \(S\)

graph TD

A[T1] --> B[T2]

A --> C[T4]

C --> D[T3]

(2). If \(S\) a serializable schedule? If not, give the reason

Yes.

(3). Is \(S\) a recoverable schedule, and why?

No, \(S\) is not a recoverable schedule. A recoverable schedule requires that for every pair of transactions \(T_i\) and \(T_j\), if \(T_j\) reads a data item \(Q\) previously written by \(T_i\), the commit operation of \(T_i\) must occur before the commit operation of \(T_j\). In this schedule, \(T_2\) reads stuName where stuID = 10, which was written by \(T_1\) at the beginning. However, \(T_2\) commits before \(T_1\), violating the definition of a recoverable schedule.

(4). Is \(S\) a cascadeless schedule, and why?

No, \(S\) is not a cascadeless schedule. A cascadeless schedule requires that for every pair of transactions \(T_i\) and \(T_j\), if \(T_j\) reads a data item \(Q\) previously written by \(T_i\), the commit operation of \(T_i\) must occur before the read operation of \(T_j\). In this schedule, \(T_2\) reads stuName where stuID = 10, which was written by \(T_1\) at the beginning. However, \(T_1\) has not committed before \(T_2\) reads the data, violating the definition of a cascadeless schedule.