4: OS Interfaces and Syscalls

OS Programming Interface

What are the system calls? They differ from different operating system. The follow table shows some system calls in Windows and Unix.

| Windows | Unix | |

|---|---|---|

| Process Control | CreateProcess()ExitProcess()WaitForSingleObject() |

fork()exit()wait() |

| File Manipulation | CreateFile() ReadFile() WriteFile CloseHandle() |

open() read() write() close() |

| Device Manipulation | SetConsoleMode() ReadConsole() WriteConsole() |

ioctl() read() write() |

| Information Maintenance | GetCurrentProcessID() SetTimer() Sleep() |

getpid() alarm() sleep() |

| Communication | CreatePipe() CreateFileMapping() MapViewOfFile() |

pipe() shm_open() mmap() |

| Protection | SetFileSecurity() InitializeSecurityDescriptor() SetSecurityDescriptorGroup() |

chmod() umask() chown() |

POSIX and LIBC

Portable Operating System Interface (POSXI) is a standard for UNIX OSes, especially its system calls.

LIBC: Overview of standard C libraries.

- POSIX APIs like

getpid()and standard C functions likestrcpy(). - Apps do not directly invoke syscalls.

- GLIBC: GNU C library.

If a software is written with only dependency to libc, it has good portability across OSes/hardware.

Case Study: Process Management

Why we need multi-process? Early motivation: allow developers to write their own shell command line interpreters.

Process in Windows

Boolean CreateProcess(char *prog, char *args).

- Create and initialize the process control block (PCB) in kernel.

- Create and initialize a new memory address space.

- Load the program

proginto the address space. - Copy arguments

argsinto memory in the address space. - Initialize the hardware context to start execution at “start”.

- Inform the scheduler that the new process is ready to run.

In reality, it’s a bit more complex. The parent process may specify the child process’s privileges, where it sends its input and output, what it should store its files, what to use as a scheduling priority.

fork() in Unix

fork() and exec(): The Unix way to create new process.

Perhaps one of the most controversial design in Unix.

fork(): Create a complete copy of the parent process, except the return value:- 0 for child process.

- The PID of child process for the parent process.

exec(): Load and execute a program from disk.- Note:

exec()does not create a new process.

- Note:

What actually have

fork()andexec()done?

fork()

- Create and initialize PCB.

- Create a new address space.

- Copy the entire memory contents from parent process to the child.

- Inherit the execution content of the parent (e.g., open files)

- Inform the scheduler that new process is ready to run.

exec(char *prog, char *args)

- Load the program

proginto the current address space.- Copy arguments

argsinto memory in the address space.- Initialize the hardware context to start execution at “start”

A typical example of how fork() and exec() are used.

1 | |

The memory contents of the child process are copied twice, would taht be a waste?

exec()is not always necessary (open a new page in Google Chrome)

wait(pid): Wait for the child process to finish execution.Signal: Terminate, stop, resume a process

Case Study: Input/Output

Computer systems have very diverse I/O devices. Having an interface for each device means the OS interface needs to expand whenever a new device is added. Unix has one interface for all of them! (“Everything is a file” - open, read, write, clos)

File Descriptor in Unix

File Descriptor (fd): a number (int) that uniquely identifies an open file in a computer’s operating system. It describes a data resource, and how that resource may be accessed.

- Each process has its own file descriptor table.

- A file can be opened multiple times and therefore associated with many file descriptor.

- More in filesystem courses.

Internally, it has everything about an opened file (where it resides; its status; how to access it; …)

Input/Output in Unix

A uniform interface for all I/O

- Uniformity:

open,close,readandwrite - Open before use

- Byte-Oriented

- Even if blocks are transferred, addressing is in bytes

- Kernel-Buffered reads/writes

- Streaming and block devices looks the same

- Read blocks process, yielding processor to other task

- Writes dose not block (even if it’s faster than device receiving data)

- Explicit close

- Garbage collection of unused kernel data structures

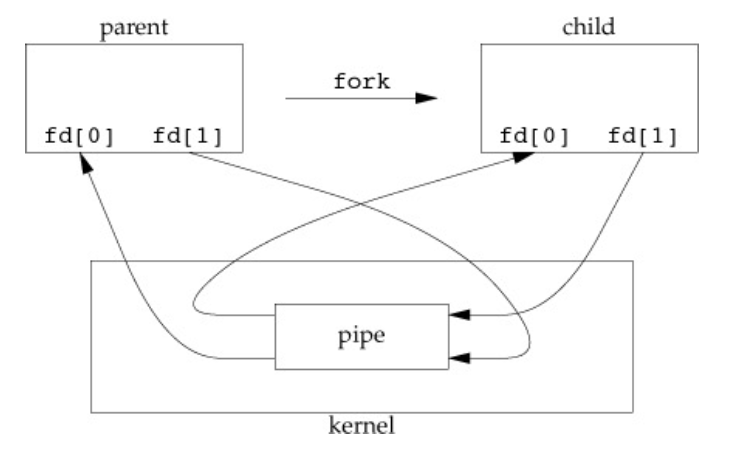

Extending the interface to inter-process communication

- Pipes: a kernel buffer with two file descriptors (reading and writing)

- Replace file descriptor for the child process

- Often used in shells

- Wait for multiple reads

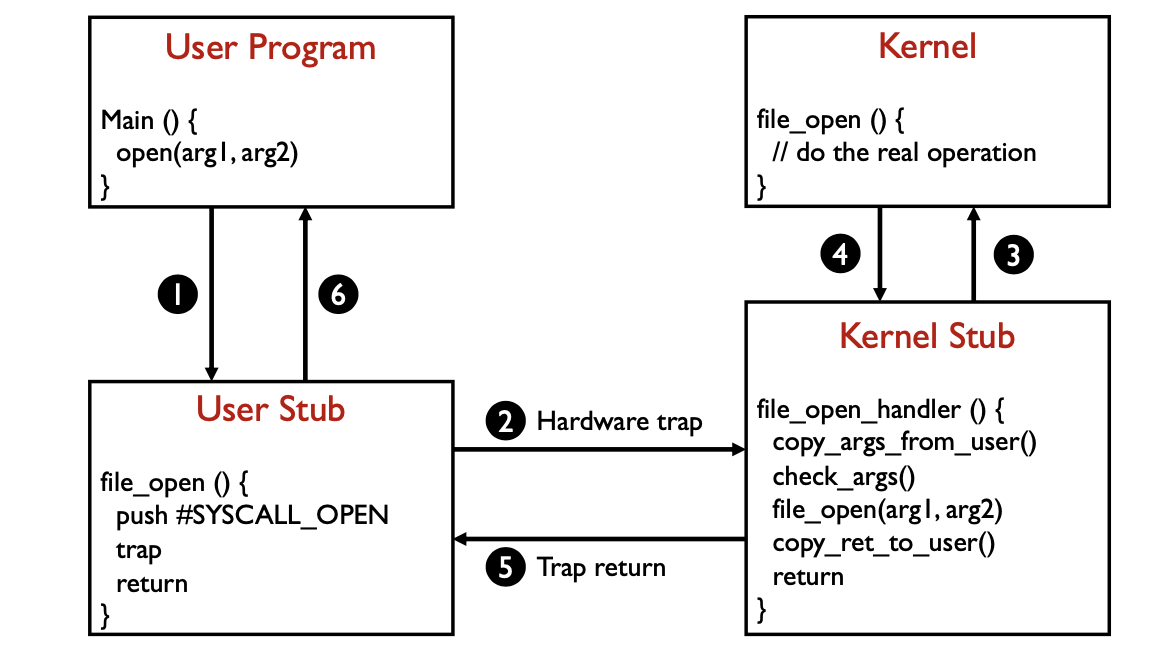

System Calls

- An illusion that kernel is simply a set of library routines.

- Actually, it’s not. They are not even in the same context!

- Names, arguments, return values.

- A key challenge: protection from user-space errors.

- What are to be checked?

User Stub

In x86

1 | |

The int instruction:

- Saves the program counter, stack pointer, and eflags on the kernel stack

- Jumps to the system call handler through interrupt vector table

- The kernel handler examines the TrapCode and calls the correct stub

Kernel Stub

Can kernel directly access the parameters without copying?

Yes.

Why parameters must be copied from user memory to kernel memory?

Avoid user modify parameters.

Can we check parameters before copying them to kernel memory?

No. User program may modify parameters.