The Kernel Abstraction

A central role of operating systems is protection — the isolation of potentially misbehaving applications and users so that they do not corrupt other applications or the operating system itself.

This chapter focuses on how the operating system protects the kernel from untrusted applications, but the principles also apply at the application level.

The Process Abstraction

Some Defintiions:

A compiler converts that code into a sequence of machine instructions and stores those instructions in a file, called the program’s executable image, what’s more, the compiler also defines any static data the program needs, along with its initial values, and includes them in the executable image.

To run the program, the operating system copies the instructions and data from the executable image into physical memory. The operating system sets aside a memory region, the execution stack, to hold the state of local variables during procedure calls. The operating system also sets aside a memory region, called the heap, for any dynamically allocated data structures the program might need.

The operating system keeps track of the various processes on the computer using a data structure called the process control block, or PCB. The PCB stores all the information the operating system needs about a particular process: where it is stored in memory, where its executable image resides on disk, which user asked it to execute, what privileges the process has, and so forth.

Dual-Mode Operation

Memory Protection

Base and Bound

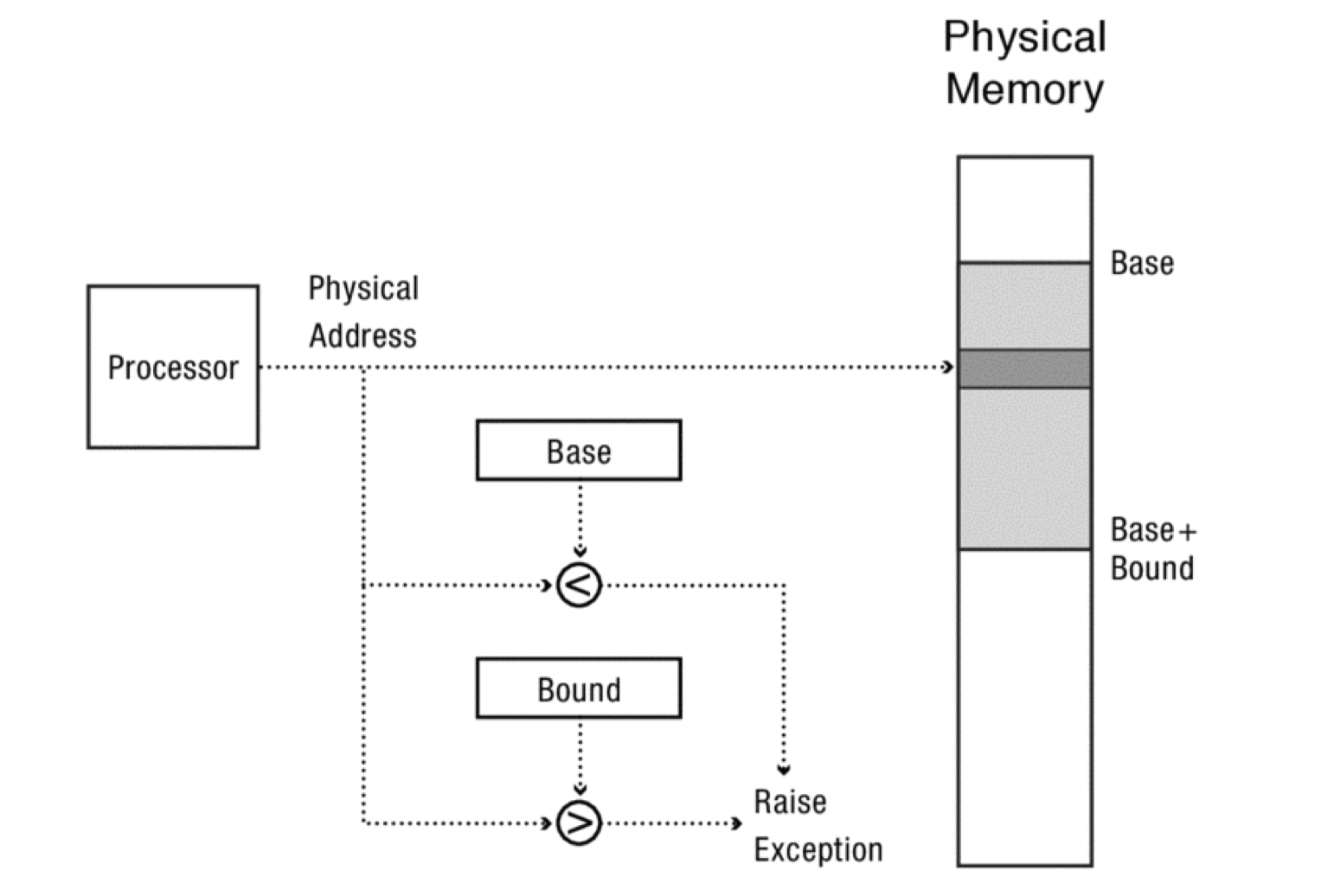

Base and bound memory protection using physical addresses. Every code and data address generated by the program is first checked to verify that its address lies within the memory region of the process.

With this approach, a processor has two extra registers, called base and bound. The base specifies the start of the process’s memory region in physical memory, while the bound gives its endpoint. These registers can be changed only by privileged instructions, that is, by the operating system executing in kernel mode. User-level code cannot change their values.

Using physically addressed base and bound registers can provide protection, but this does not provide some important features:

Expandable heap and stack.With a single pair of base and bound registers per process, the amount of memory allocated to a program is fixed when the program starts. Although the operating system can change the bound, most programs have two (or more) memory regions that need to independently expand depending on program behavior. The execution stack holds procedure local variables and grows with the depth of the procedure call graph; the heap holds dynamically allocated objects. Most systems today grow the heap and the stack from opposite sides of program memory; this is difficult to accommodate with a pair of base and bound registers.

Memory sharing. Base and bound registers do not allow memory to be shared between different processes, as would be useful for sharing code between multiple processes running the same program or using the same library.

Physical memory addresses. When a program is compiled and linked, the addresses of its procedures and global variables are set relative to the beginning of the executable file, that is, starting at zero. With the mechanism we have just described using base and bound registers, each program is loaded into physical memory at runtime and must use those physical memory addresses. Since a program may be loaded at different locations depending on what other programs are running at the same time, the kernel must change every instruction and data location that refers to a global address, each time the program is loaded into memory.

Memory fragmentation. Once a program starts, it is nearly impossible to relocate it. The program might store pointers in registers or on the execution stack (for example, the program counter to use when returning from a procedure), and these pointers need to be changed to move the program to a different region of physical memory. Over time, as applications start and finish at irregular times, memory will become increasingly fragmented. Potentially, memory fragmentation may reach a point where there is not enough contiguous space to start a new process, despite sufficient free memory in aggregate.

这段内容主要讨论了基于物理地址的基址和界限寄存器实现内存保护的方式及其局限性,具体包括以下几点:

可扩展的堆和栈:仅依靠一对基址和界限寄存器,程序启动时的内存区域是固定的,无法满足堆和栈需要独立扩展的需求。

内存共享问题:基址和界限寄存器方法不能实现多个进程之间的内存共享,比如共享代码或库,这在多进程环境下是一个重要功能。

物理内存地址问题:程序在编译时所有地址均相对于可执行文件的起始位置(即从零开始),而加载到物理内存时,必须调整所有全局地址指令,使得加载过程极为复杂且低效。

内存碎片问题:一旦程序加载,就难以迁移,因为内部的数据结构(例如寄存器中的指针)需要重新调整,这会导致内存碎片问题,最终可能无法分配足够连续的内存空间启动新进程。

整体来说,文章在说明虽然基于基址和界限寄存器的内存保护机制可以提供基本的保护,但它在现代操作系统中存在诸多限制,不适应现代应用程序对内存灵活性和共享能力的需求。